Right now our Sun is in the main sequence stage, steadily fusing hydrogen into helium in its core and releasing huge amounts of energy. This balance between the outward push of fusion and the inward pull of gravity keeps the Sun stable. It’s been shining this way for about 4.6 billion years and will continue for another ~5 billion.

When the core hydrogen is mostly gone, fusion slows. Gravity compresses the core, heating it up, while the outer layers swell. The Sun will become a red giant, expanding so large that Mercury and Venus will be swallowed, and Earth scorched by its outer atmosphere.

As the core grows hot enough, helium begins to fuse into carbon and oxygen. This is a brief but energetic phase — a few hundred million years compared to billions on the main sequence. The Sun will shine even more brightly, still as a red giant.

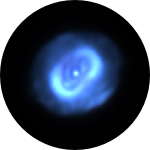

When the helium is used up, the Sun will no longer have the heat and pressure to sustain fusion. The outer layers will be gently blown away into space, forming a glowing shell of gas — a planetary nebula. This is not an explosion, but a graceful shedding, lit up by the star’s hot core.

At the center, the Sun’s leftover core will be revealed — a hot, dense white dwarf, about the size of Earth but with half the Sun’s mass. It no longer fuses elements, but shines faintly from stored heat. Over billions of years, it will cool and fade into a dark black dwarf (though the universe isn’t old enough for any to exist yet).

Poetic thought: One day our Sun will draw its last breath, and in doing so, it will paint the heavens with a planetary nebula — a cosmic farewell glowing across the galaxy.

What will this look like? Well, the good news is that we don’t have to wait because we can see planetary nebulae now…. somewhere in the Milky Way, a Sun-like star gently sheds its outer shell and lights up a new planetary nebula about once every 12 months or so, and each glows for about 25,000 years before fading back into interstellar space.

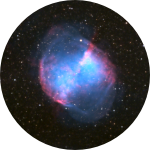

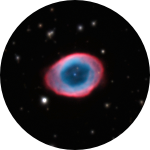

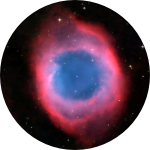

Of the thousands of planetary nebulae estimated to be in our Milky Way now, only about 20–30 are bright enough and close enough to be fairly easy to see in modest telescopes from the northern hemisphere. These well-known planetary nebulae, like the Dumbbell Nebula (M27), the Ring Nebula (M57) or the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293), are previews of our Sun’s fate and are available to stargazers on clear, dark nights.

Tips for Exploring Planetary Nebulae (PN)

⭐️ Use a telescope, the bigger the better

Most planetary nebulae are dim and tiny, often less than 1 arcminute across (the Moon is 30 arcminutes). A telescope is needed to reveal their true form — rings, shells, halos, central stars, knots, or lobes. These features only appear with enough magnification and light-gathering power.

⭐️ View under dark skies

Even though some PNs are bright, their surface brightness is low, so light pollution can erase them. The darker your site, the more planetary nebulae you’ll see — and the more structure you’ll notice.

⭐️ Know Exactly Where to Look

Planetary nebulae are often tiny and can masquerade as faint stars. Use a detailed star chart or app to star-hop precisely. Famous examples like the Ring Nebula (M57) sit between well-known stars, but others need careful navigation.

⭐️ Start with Low Power but Watch for the “Not a Star” Effect

Many small PNs will resemble stars under low power but, look carefully and compare them to nearby stars and you’ll see that a planetary nebula often stays slightly “fuzzy” while nearby stars snap to sharp points. This subtle difference is often the giveaway.

⭐️ Once found, Zoom In

Once you’ve confirmed the spot, increase magnification — this often makes the nebula stand out from nearby stars, revealing its round shape or even structure.

⭐️ Employ Averted Vision

Look slightly to the side of the nebula instead of directly at it. The more light-sensitive parts of your eye can reveal faint details such as extended halos or brighter edges.

⭐️ Use a Nebula Filter

An OIII filter (or a UHC filter) screwed into the bottom of an eyepiece can be transformative. It dims starlight but boosts the glow of the nebula, especially for faint shells or halos. This is one of the most useful tools for observing planetary nebulae with modest telescopes.

Here’s a guide to 16 of the most popular planetary nebulae visible to stargazers in the Northern Hemisphere:

| Top PNs |

Name |

Season |

Brightness

Magnitude |

Angular

Size |

Description |

|

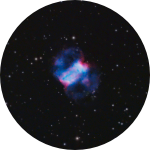

Dumbbell Nebula (M27) |

Summer |

+7.09 |

8.0’ x 5.07’ |

One of the brightest and easiest PNs, visible even in binoculars. |

|

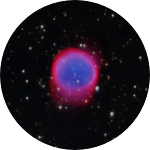

Ring Nebula (M57) |

Summer |

+8.20 |

1.4' x 1.1’ |

Iconic doughnut-shaped PN, easy to find between the stars of Lyra’s parallelogram. |

|

Helix Nebula (C63) |

Autumn |

+7.59 |

14.7’ x 12’ |

The largest planetary nebula in the sky; looks like a cosmic eye under dark skies. |

|

Owl Nebula (M97) |

Spring |

+9.80 |

3.4' x 3.3' |

Round, ghostly, with “eyes” visible in larger scopes. |

|

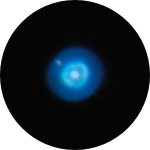

Blue Snowball Nebula (C22) |

Autumn |

+8.30 |

0.5' x 0.5' |

Compact, very bright; striking bluish color in small scopes. |

|

Saturn Nebula (C55) |

Autumn |

+7.80 |

0.5' x 0.4' |

Resembles Saturn’s shape with high magnification. |

|

Eskimo Nebula (C39) |

Winter |

+9.19 |

0.8' x 0.7' |

Looks like a human face inside a fur parka hood — compact and bright. |

|

Ghost of Jupiter Nebula (C59) |

Spring |

+7.3 |

0.7' x 0.6' |

Bright oval planetary nebula that resembles a pale, featureless disk — like a miniature version of the planet Jupiter’s ghostly image drifting in space. |

|

Cat’s Eye Nebula (C6) |

Summer |

+8.10 |

0.4' x 0.3' |

Famous for its intricate inner structure in photos; tiny but very bright visually. |

|

Skull Nebula (C56) |

Autumn |

+10.39 |

4.0' x 3.5' |

Large and faint with an irregular, patchy appearance; under dark skies it can look like a ghostly skull with darker voids where the “eye sockets” would be. |

|

Blinking Planetary Nebula (C15) |

Summer |

+8.89 |

2.1' x 2.1' |

Central star makes the nebula appear and vanish with direct vs. averted vision. |

|

NGC 2438 |

Winter |

+11.50 |

1.2' x 1.1' |

NGC 2438 in Puppis is a small, PN that is unique in how it appears to be hiding within the bright stars of the open cluster M46. |

|

Little Dumbbell Nebula (M76) |

Fall Winter |

+10.10 |

2.7' x 1.9' |

Compact twin-lobed nebula that looks like a smaller, dimmer cousin of M27; appears rectangular or bar-shaped in modest telescopes. |

|

Snowglobe Nebula (NGC 6781) |

Summer |

+11.60 |

1.9' x 1.8' |

Striking round, ghostly bubble of nebulosity; often compared to a fainter, softer version of the Ring Nebula, with a nearly circular outline. |

|

Cleopatra's Eye (NGC 1535) |

Winter |

+9.39 |

0.8' x 0.7' |

NGC 1535 is a compact and colorful planetary nebula in Eridanus that shines like a tiny bluish disk with a bright inner core and faint halo, resembling a cosmic eye./td>

|  |

Little Gem Nebula (NGC 6818) |

Summer |

+9.39 |

0.4' x 0.2' |

NGC 6818, the Little Gem Nebula, is a challenging planetary in Sagittarius that appears as a tiny bluish-green disk sparkling against the rich backdrop of the Milky Way./td>

|

While most stars in our galaxy, including our Sun, will end their lives in a gentle way by forming planetary nebulae, not all stars end so quietly. The very massive ones — at least eight times the Sun’s mass — live fast and die violently. Their cores collapse once they can no longer fuse elements for energy, triggering a titanic supernova explosion. In an instant, the star blows apart, outshining entire galaxies and scattering heavy elements into space that make planets — and life — possible. What remains is either a neutron star, no bigger than a city, or, if the mass is great enough, a black hole.

Is it possible to view supernovas too? Yes, check these out:

| Super-novas |

Name |

Season |

Brightness

Magnitude |

Angular

Size |

Description |

|

Crab Nebula (M1) |

Winter |

+8.39 |

6.0’ x 4.07’ |

Messier 1, the Crab Nebula in Taurus, is the remnant of a supernova seen on Earth in 1054, glowing with tangled filaments of gas and housing a rapidly spinning neutron star at its heart. |

|

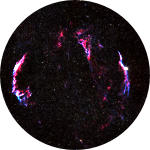

Veil Nebula |

Summer |

+5.00 |

Western: 70' x 6'

Eastern: 60' x 30' |

The Veil Nebula in Cygnus, split into its bright Western and Eastern (NGC 6992/6995) arcs, is a vast supernova remnant from a massive star that exploded thousands of years ago. |

Each night the sky is alive with wonders — including stars dying — waiting for stargazers to look up, and enjoy the incredible show. |